|

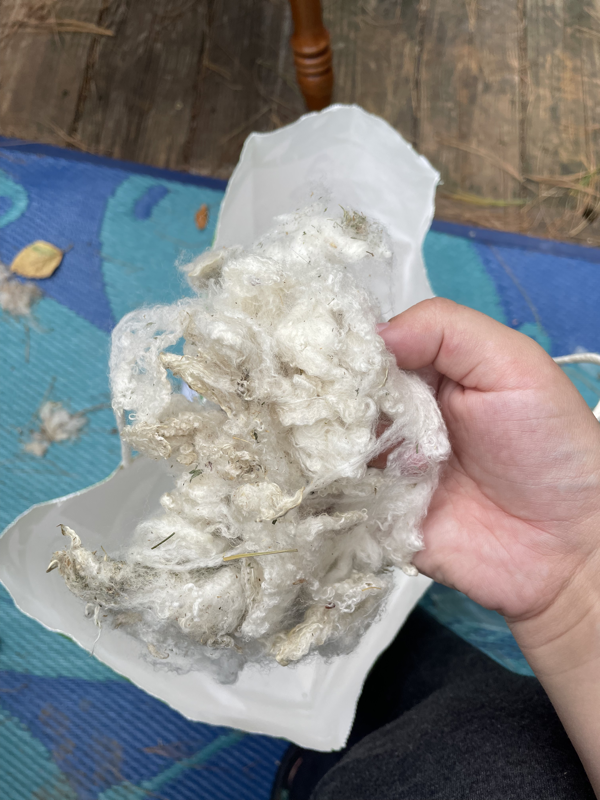

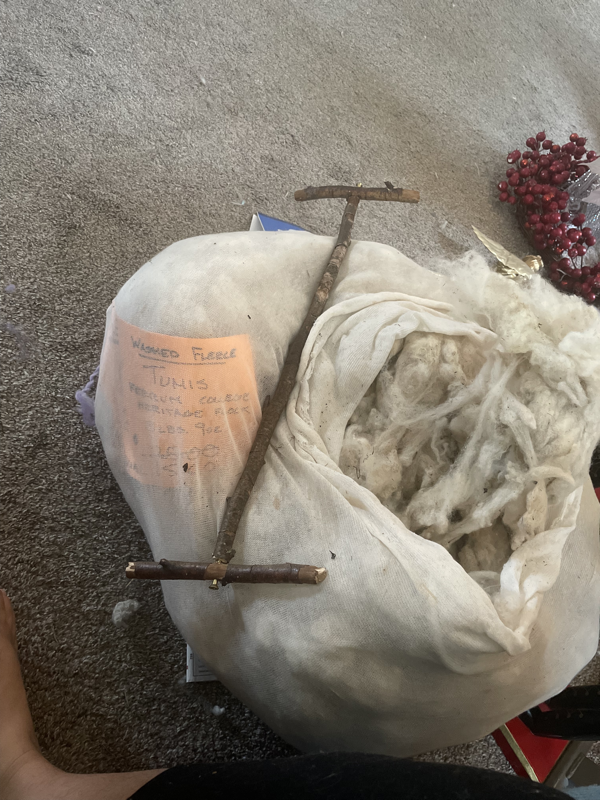

Today in class at the WBFP, Mary Berry asked us a question--an essential question that we’ve been wondering since our first class, Homecoming: Good Work is Membership--How does one become native to a place? Earlier in the past week, I wrote about how the concept of “home” has really been a depressing concept in my life. Once we moved from our first house, I will never forget the isolation I felt, move after move, planning to move, unpacking repacking. Even now that I finally feel I have a safe, creative and uplifting house and household, I know it’s not the forever home--and I honestly don’t want it to be. I need to be somewhere I can connect to nature and my spirit guide, somewhere where the wind flies free and the hills run thick with tall, perennial grasses. Somewhere I can work with the earth, grow my own homeland security, and of course raise woolie wonders for fiber arts. While Mary asks how one becomes native to a place, I sit here in limbo, wondering. I wonder what is the proper involvement for one to have if they know they’re going to leave one day? Ultimately, how does one live this way?

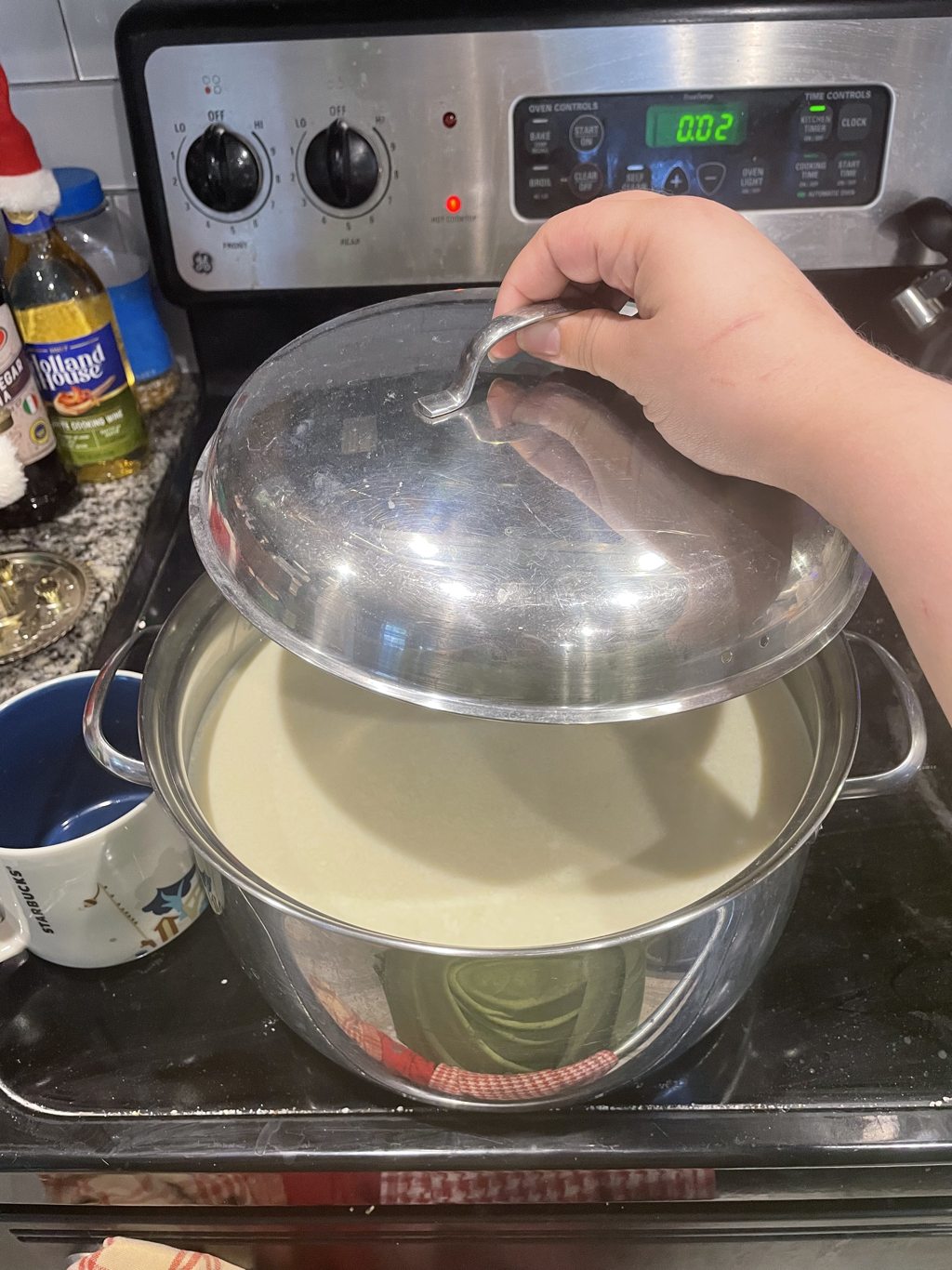

It’s an uncomfortable topic for me, this feeling of homelessness within a home. And thus, in the tradition of procrastinating thinking about uncomfortable things, I think I’ll put it off. What I do want to talk about is Mary’s question, How does one become native to a place? You might know I just finished reading Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall-Kimmer, and have been raving over it ever since. Whelp, it’s time for some more raving! Braiding sweetgrass is a book of traditional ecological knowledge (Native wisdom) and helps us all find our wild side, our peaceful side. She urges the reader to look within and look without the self, look at yourself from the world’s perspective. I read this book for fun, for its beauty, for research, and to understand. I think understanding others is something we work towards our whole life, and are constantly starting over with. Wall-Kimmer writes of understanding, “Native scholar Greg Cajete has written that in indigenous ways of knowing, we understand a thing only when we understand it with all four aspects of our being: mind, body, emotion, and spirit,” (47). She also writes that in order to preserve this indigenous wisdom, and these indigenous ways, we need to practice them. Wall-Kimmer suggests that we shouldn’t copy the old indigenous ways and ceremonies out of context, and also that we can create new ceremonies. These new ceremonies, of course, need to--no, they have to have a lot of meaning, thought, and selfless good-intentions behind them. They should be meaningful to our culture and our identity and ultimately express gratitude, selfless gratitude. I feel that of this wisdom come three important themes: understanding, ceremony, and gratitude. Now, we lay the framework for becoming native to a place. Wall-Kimmer covers this topic quite a lot in her book, but most intensely in this section I quote. She writes, “To be native to a place we must learn to speak its language,” (Wall-Kimmer 48). Beautiful. But what does it mean? I’ve been thinking about this all day, and what I think “learning to speak the place’s language” might mean is truthfully understanding. This is good work within the farmscape, work worth doing. It involves listening, identifying species, seeing the nature of the creatures, feeling the changes in the weather and the season, waiting for the right moment to harvest, getting to work, and being thankful for it all. Did I hit all the senses? Oh! Smelling the flowers, the grass, the dinner cookin on the stove and wafting down to your rumbling belly. Tasting your home grown medicine and food, knowing that it is a gift from the earth. These gifts should be given willingly, not stolen by humans. You will know when gifts are at your feet. You will know them by their beauty and love. One thing I really admire is when Wall-Kimmer is describing the sounds that she hears, her own sensory exploration, and something more--something that is not me, for which we have no language, the word less being of others in which we are never alone. After the drumbeat of my mother's heart, this was my first language,” (48). We as humans seem to be quite (and i do mean quite) strict with what we consider to be language. Wall-Kimmer states this strictness in much more blatant terms than I would venture to use, “The arrogance of English is that the only way to be animate, the only way to be worthy of respect and moral concern, is to be a human,” (57) but her word choice is honest. We really only view ourselves (human beings) as having culture, and even still, often bash those with cultural differences from our own. But what about the whales?! Who swim in family groups, all the while singing ‘songs’ to communicate. We really do recognize whalesong as distinct languages today, as we rightfully should. What about the birds? What about the bees? What about our pets? How do ants organize themselves into lines? Language. It just might have different grammatical rules--very different indeed, “A language teacher I know explains that grammar is just the way we chart relationships in language,” (Wall-Kimmer 57). She goes forward with an unlikely example, “The fact is, maples have a far more sophisticated system for detecting spring then we do. There are photo sensors by the hundred in every single bud, packed with light absorbing pigment called phytochromes,” (Wall-Kimmer 65). Reading the language of the changing of the seasons is in our bones as earthlings. I think when we say earthlings, we often are thinking just humans. We so often forget the other creatures on our planet. Sensing spring by the language of light--what a beautiful thing. I think this is another big key to becoming native to a place, not reducing the existence of life (sentient or not based on your own beliefs) to a commodity, a ‘thing’. “ In English, we never referred to a member of our family, or indeed to any person, as it. That would be a profound act of disrespect. It robs a person of self-worth and kinship, reducing a person to a mere thing. So it is that in Potawatomi and most other indigenous languages, we use the same words to address the living world as we use for our family. Because they are our family,” (Wall-Kimmer 55). I feel this deeply. “They are our family.” Which is perhaps why I am tentative to put down roots at my house, here. I want so badly to feel the familiar relations of my earth, those I felt in the Pisgah Forest and the Blue Ridge Mountains. My heart is torn between wanting to be in two other places than my own place. I am so thankful for the safety it provides, the creative space, the loving memories, but it feels devoid of Life. Yes there is are garden notions, a yard (and I had to let the veggie garden go because of mental health difficulties this summer.) But all these things function under human auspices and human rules. And let me tell you, our rules are strict and our auspices often cruel and dangerously carried out. They do not serve well our lawns, our pollinators, our birds, our native plants and host plants for the base of the food chain? We are high on our narcissistic appearances. We go low with our blows to ecology, to mother earth. Wall Kimmer quotes one of the most important philosophers of our time (And a favorite of mine), Father “Thomas Barry has written, “we must say of the universe that it is a communion of subject, not a collection of objects,” (56). We cannot use and abuse our family, that is bad form, uncalled for, and altogether cruel. Now, I’d rather talk about something cheerful and uplifting. Yesterday was the tobacco harvest for John Logan Brent, The county Judge Executive for Henry County, my hopeful future homeplace. And boy did I feel connected to the tobacco. You may or may not know, but I am a smoker and if you do not wish to read this part about tobacco, skip to the stars! Today’s work housing tobacco made me really think deep about its history and cultural impact. I was also thinking deeply about its prevalence in my own life and my own choices regarding it. While I know that it is more often than not fatally harmful health-wise, it really has become a big part of my life and a form of ritual. I also acknowledge and accept the chances of health issues that come with this ritual of mine… Anyhow, I have been thinking a lot about where I get my tobacco recently. I used to use American Spirits, light blue, which are “grown in the US”. Most of our tobacco is not grown in the US, it is mostly grown in China, India, and Brazil. Knowing it is imported for very little, I switched to a loose leaf tobacco with more flavor, Drum Tobacco halfzware shag, which I understood was European. Upon further wikipedia research, I learned that this tobacco was not exactly what I thought it was. It is a mix of dark and light tobaccos, but as far as what kind it is and where it is grown, wiki notes, “The two versions of Drum are made in different locations and have different sensory properties. European Drum is barrel-cured in the Netherlands using a centuries-old process, whereas the American version is made at the Top Tobacco factory in North Carolina.” Inspecting my packaging, it notes that it is labeled as a mix of both foreign and US tobacco. Sourcing tobacco is hard, yall. I feel like for me, something so serious (deadly serious) as smoking tobacco should have the option of knowing what you’re smoking. Especially with cigarettes that are not organic, and with the use of chemical pesticides and such. Which is why I’m excited, come November, to try this locally sourced tobacco--grown and gifted by a friend, and harvested together with some of the finest people this side of anywhere. Not a smart decision, but a decision with a lot of thought and meaning behind it. Some further Wiki exploration unearthed these cool facts as well, “Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the Nicotiana genus and the Solanaceae (nightshade) family, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of the tobacco plant. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the chief commercial crop is N. tabacum.” Wikipedia lists almost 20 different cultivars and varieties, but it seems the number is different everywhere ya look. John Logan said he grew two different varieties of tobacco this year, burley and a cigar wrapper variety. Now, as a lover of KY, and a lover of tobacco, burley is the one. Wiki says, “the origin of White Burley tobacco was credited to a Mr. Webb in 1864, who grew it near Higginsport, Ohio, from seed from Bracken County, Kentucky. [...] In the United States, it is produced in an eight-state belt with approximately 70 percent produced in Kentucky.” It’s a part of our culture, especially in agrarian and rural communities. John Logan didn’t really say what variety the cigar wrapper tobacco was, but upon further research, I have deduced that it might have been Corojo tobacco. “Recently, pure Corojo seed has been propagated in Western Kentucky as the F1 generation Kenbano tobacco in 2007.[2] Currently the so-called "Kenbano" tobacco seed is being raised for future production of hand-made cigar blends.” I thought this was very cool. Questions remain. What happens to the tobacco once it is sold? What is its journey from cured leaf to value added product? ***************************** Regardless, I sit here, proud of the work I did--the work we did, work worth doing. Another ceremony I want to talk about is my ceremony of writing, my ritual, my passion. I’m debating applying for further schooling in either Linguistics or Creative Writing after graduation from the WBFP of Sterling College (VT). I know that whatever I do in life, wherever I go, whoever I am with, I will always write. I will never tire of learning new words and hearing their stories and meanings. I will never tire of playing with rhythm and rhyme, words, language, and languages. Wall-Kimmer writes of a speaker of the language group Anishinaabe. She talks about a word in Anishinaabe that in all its technical vocabulary, western science has no such term, no words to hold this mystery. “You would think that biologists, of all people, would have words for life,”(49). Different words in different languages have different meaning and cultural significance. She continues on about the remaining members of her tribe, who is still speak Potawatomi, “I counted them as they filled the chairs. Nine. Nine fluent speakers. In the whole world. Our language, millennia in the making, sets in those nine chairs,” (Wall-Kimmer 50). This made me think of the geology of linguistics. How many myriad of languages have we lost already? Each had their own meanings behind each word, words for phenomena we don’t have words for today. How many languages are we losing today? What stories then pass on to the stars? It is a very despairing thought for someone who loves all manner of words, story, language. Wall Kimmer continues, “We are the end of the road. We are all that is left. If you do not learn, the language will die,” (50). If we do not use and practice these ceremonies of language, they will be lost forever. But it’s not just the words that will be lost, she says. “The language is the heart of our culture; it holds our thoughts, our way of seeing the world. It’s too beautiful for English to explain” (Wall-Kimmer 50). And thus we make our new ceremonies, becoming native to a place by learning its language, “How lonely those words will be, when their power is gone. [...] So now my house is spangled with Post-it notes in another language, as if I were studying for a road trip abroad. But I’m not going away, I’m coming home,” (Wall-Kimmer 51).

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Quilt Update!

IronweedDisco Chicken of Love

sTate fair ready!seed starting 2019ky state fair quiltWHOTH Embroideryseashell casTleswhoth blanketedible goodnessAuthorA sustainability major at U of L, beginning farmer, crafter, and writer. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed