|

Please enjoy my video of our yearly trip to the fiber festival! It is the highlight of fall for my family—I have been going since 2018 and have shared my love for the festival with family and friends from around the country, as well as made new friends. Every year I learn so much, and get so inspired. I hope to share that with you, so thank you for watching!

1 Comment

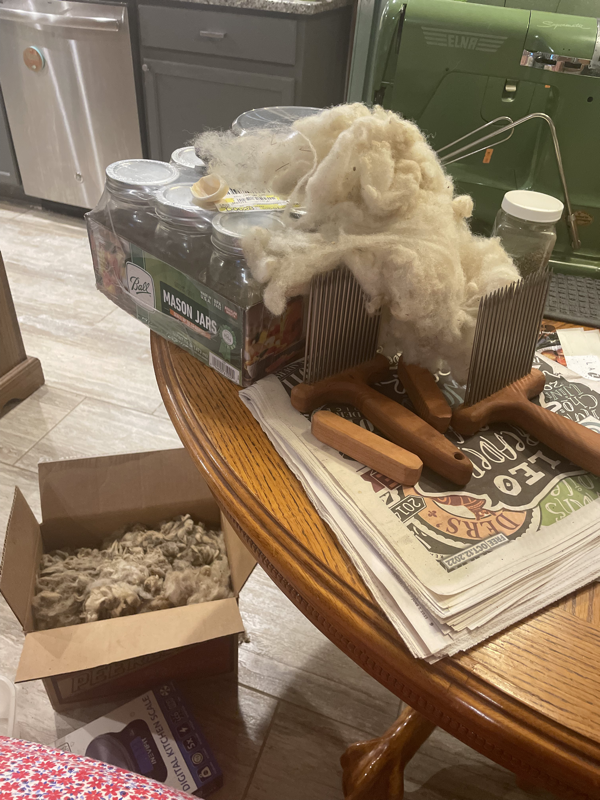

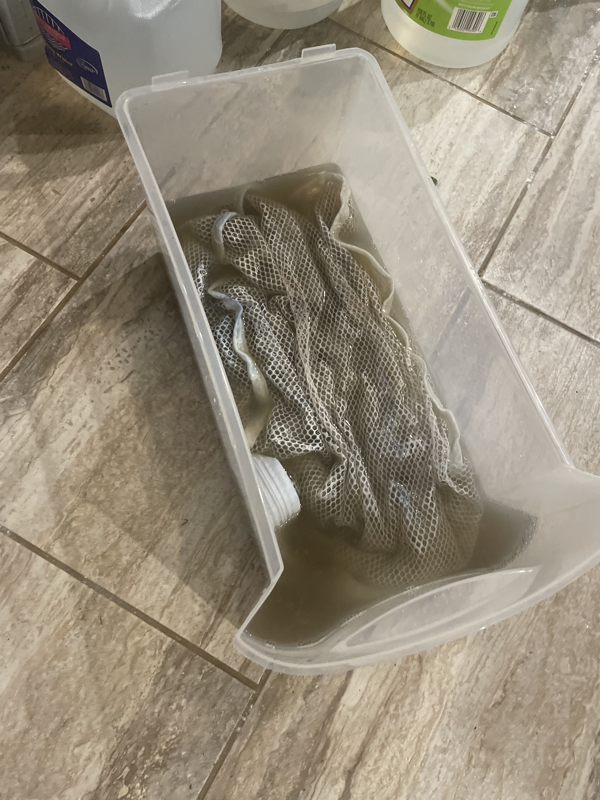

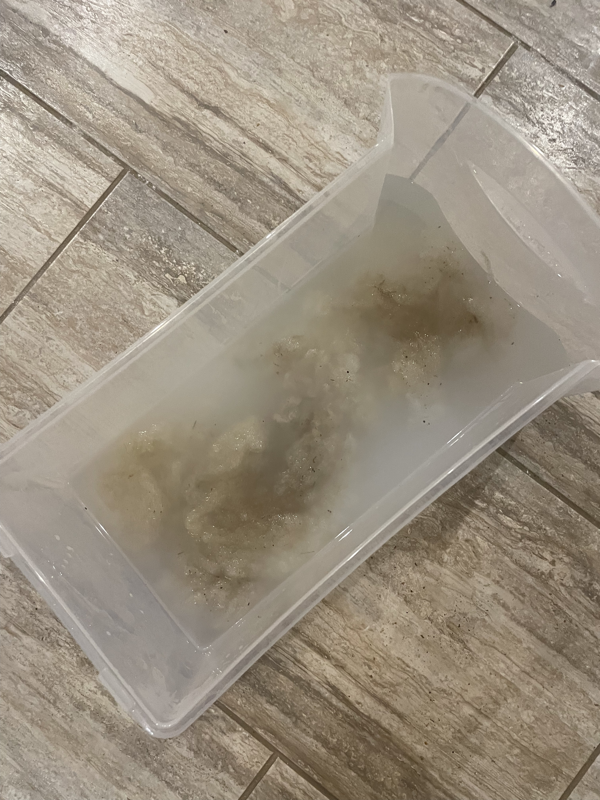

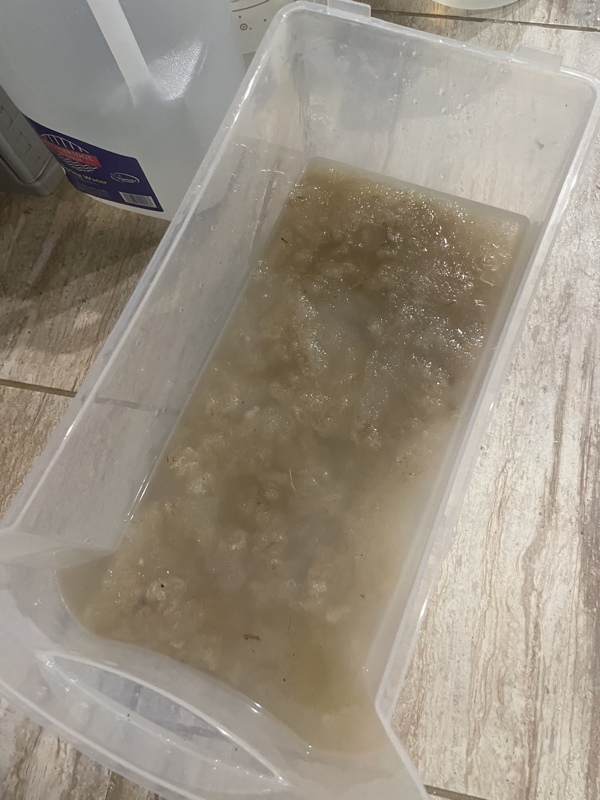

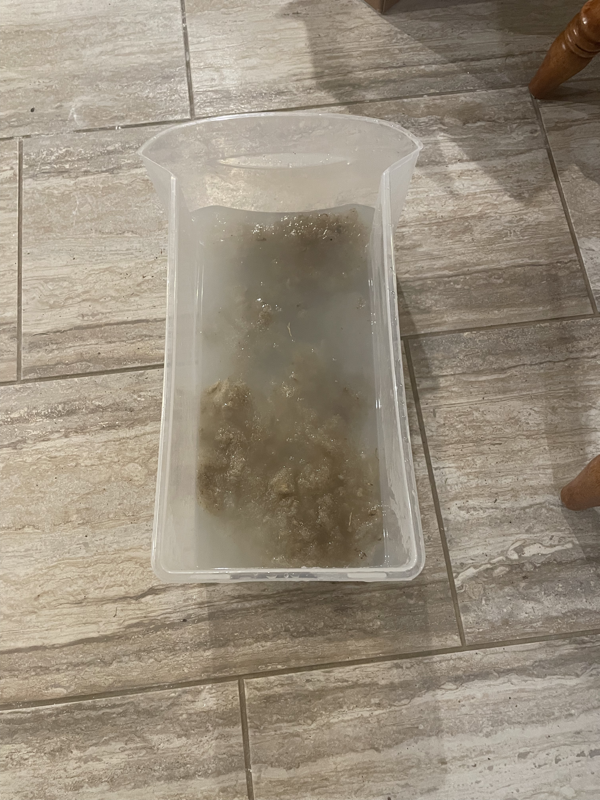

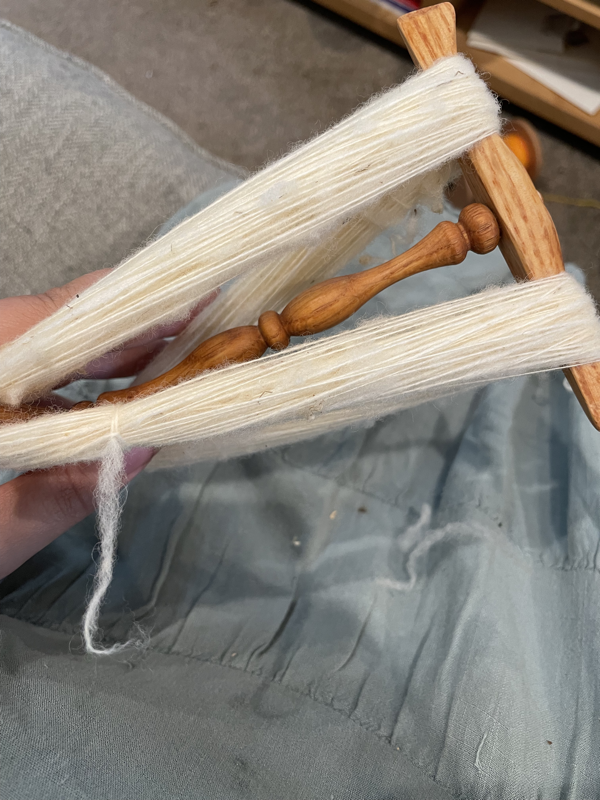

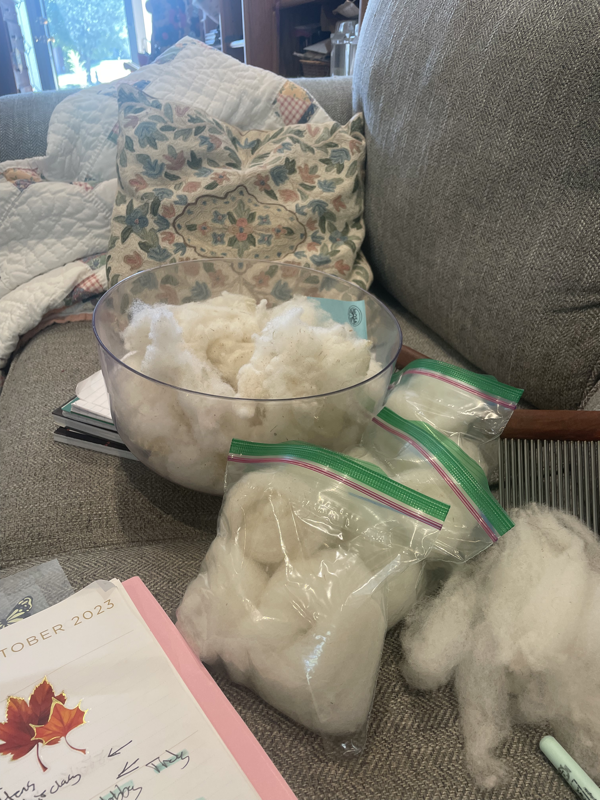

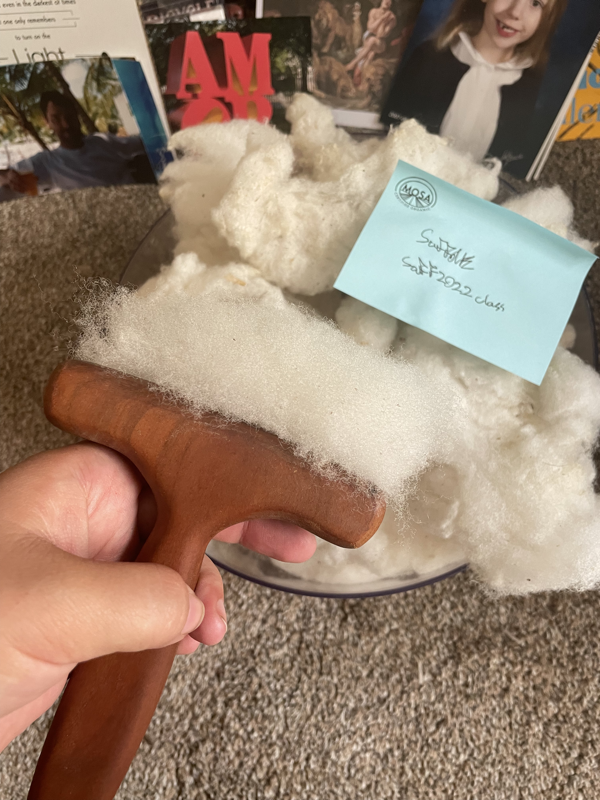

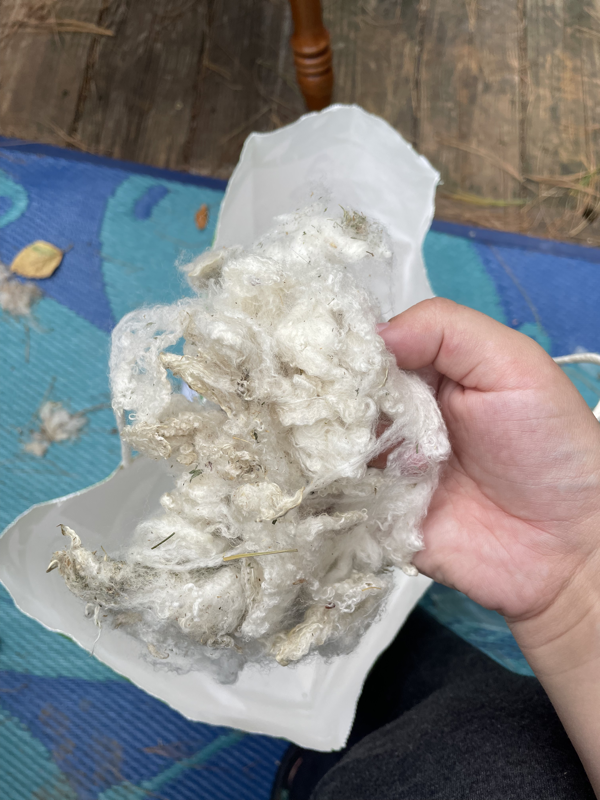

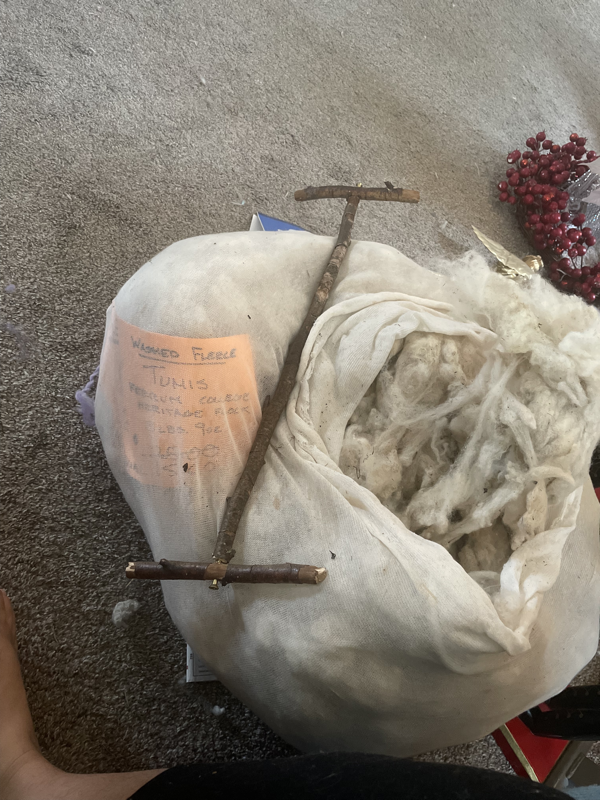

Gulf coast native was the first raw wool I worked with on my own. I purchased it via a wool group on Facebook from a woman in Alabama. I decided to comb the raw wool before washing, just because the dust, dirt, and VM were very heavy.

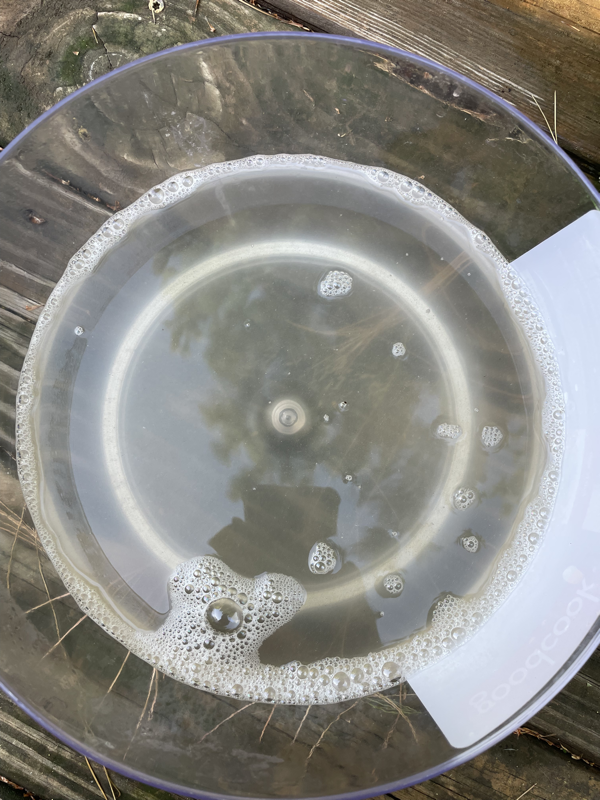

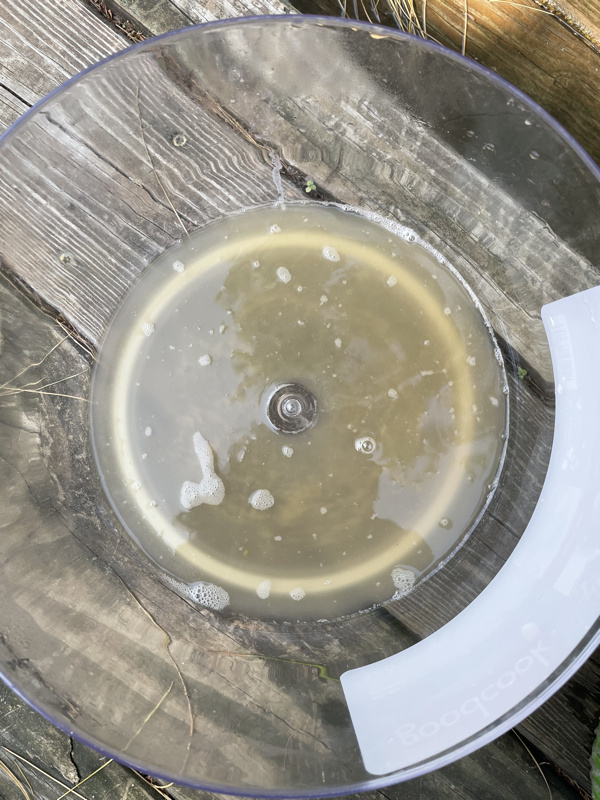

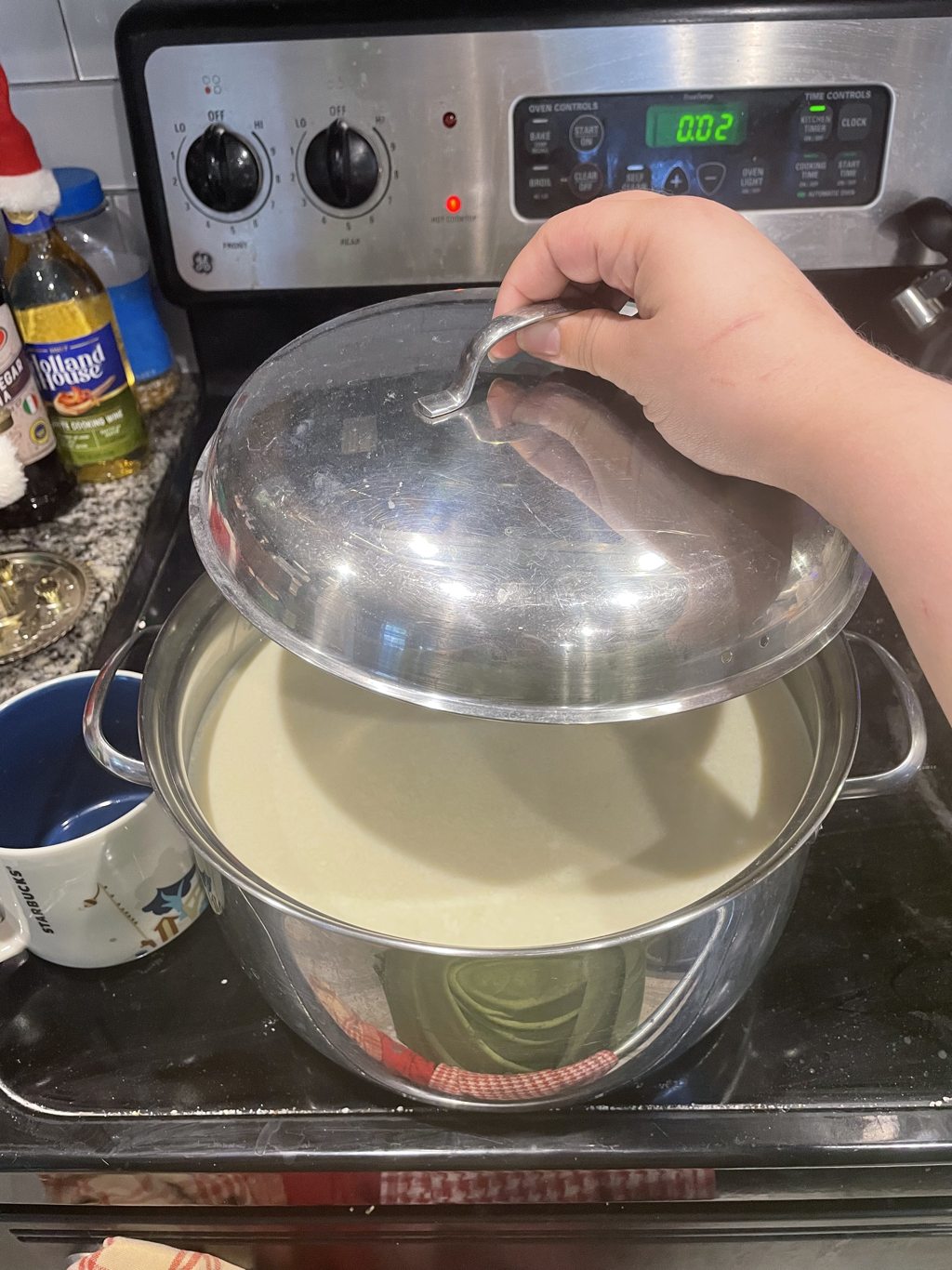

I chose to work with this breed for two reasons: availability, and conservation. The breed caught my eye—gulf coast native is a critically endangered sheep breed on the Livestock Conservancy conservation breed lists. For sheep, the movement to support demand for these endangered sheep is s campaign called “shave em to save em” or “shear em to save em”. Conservation of heritage and ancient livestock breeds is a bit different than with wild species. Livestock differ from wild animals as there is a demand to grow more of them in a domestic setting. If there’s no reason to utilize these animals, sadly, there’s actually no reason to have them. Luckily, sheep are happy to give us their wool once or twice a year, to cool off from their heavy heavy sweaters and bounce around the fields all clean and free. Also, I chose this breed because it was available, and better yet, for a low price. I got a small fleece, 1.8 lbs and was so thrilled. It washed up beautiful in Unicorn power scour , and after drying, with a second comb it was absolutely beautiful. After processing a few breeds, I decided that adding some rosemary essential oil to the wash really conditioned the wool better than unicorn alone—which felt like maybe it stripped some of the natural oils from the GCN rather than just removing excessive lanolin. I wasn’t that surprised that this fleece had a lot of VM as GCN is a native landrace, survival breed of sheep. The early North American explorers who came to the gulf coast brought over some of these sheep which adapted to the climate and pretty much naturalized themselves. They are hardy. I was surprisingly thrilled when the finished yarn showed a beautiful luster, and as the Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook says, it does take up dye well. I gifted my first skein to our fiber friend, Nancy, who watched over my great wheel for a few months. Welcome to this month’s discussion of my crafting adventures! Again, this month was a mid-month discussion, so I went over both Finished Objects (FO’s) and unfinished objects (UFO’s). Who all here would be interested in a UFO Night?? A crafting night of togetherness? Comment if you’re interested! Enjoy!

Suffolk are a “Down” wool breed, which means not that their fibres are technically (in the scientific ecological fiber world) the same as “downy fiber” like goose down or qiviut. The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook reveals the “Down” name comes from a county in Northern Ireland.

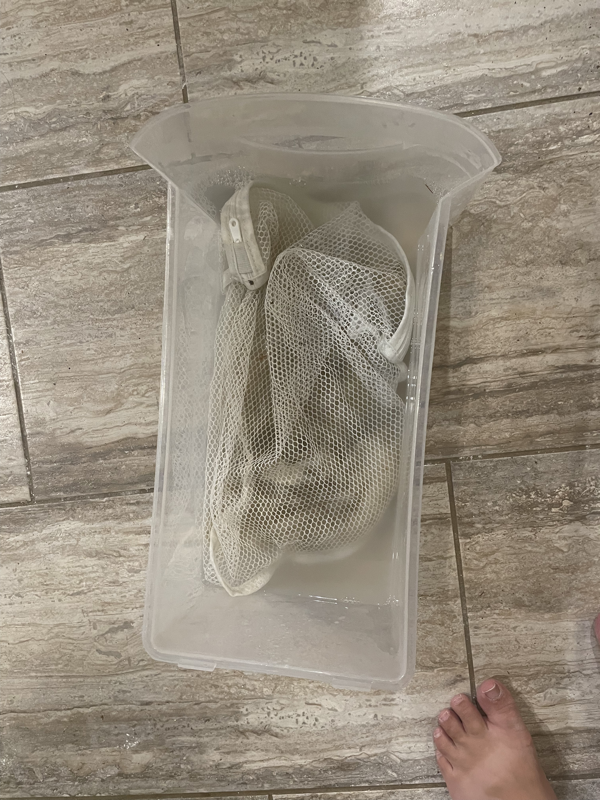

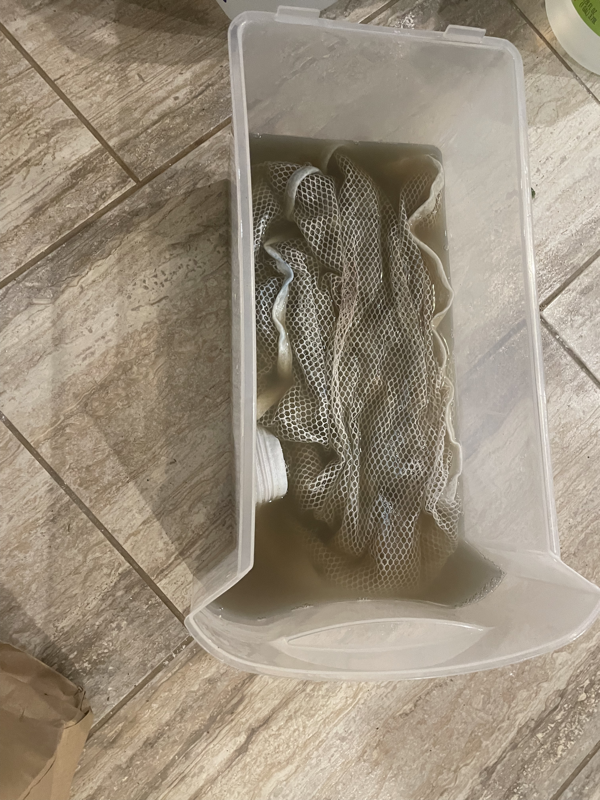

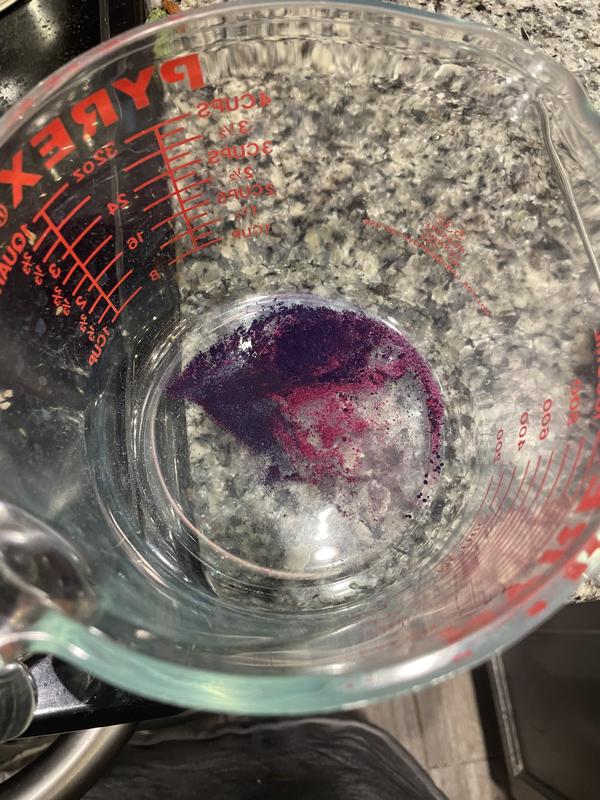

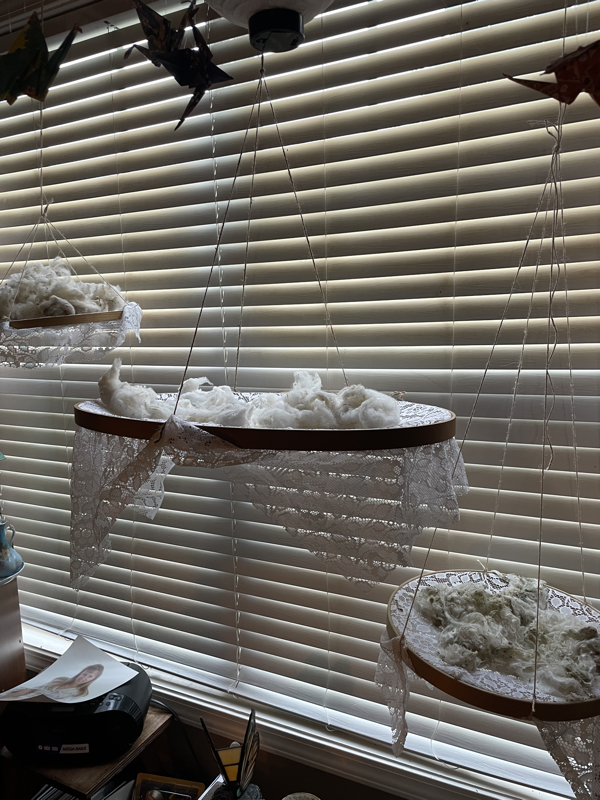

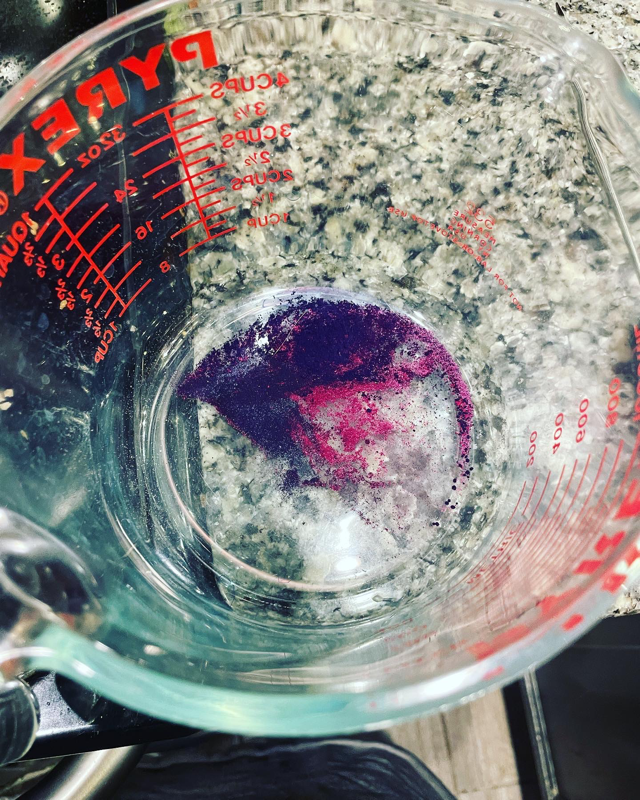

One of the interesting things the Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook talks about is breeding and genetics. The Suffolk breed is also related to Norfolk and Arcotts. The Suffolk I have was most likely grown in the US. Suffolk is one of the two most popular wool breeds in the country because they are a good choice for a dual purpose breed. The wool, however, is apparently not very popular for hand spinning. I can attest, at the KY state fair, one farmer came up to our Spinning group as we were demonstrating and said, “is there even a market for wool nowadays?” (Talking about his Suffolk wool) Every one of us was like— “YES!!” Then, he mentioned they were Suffolk, and several of the women said “well, that’s only good for felting”… this week I got up close and personal with some though, and spun it a few different ways, so I do have a happy report! The majority of US Suffolk wool is sold in wool pools which kind of work the same way tobacco sales worked before the Tobacco Program. It is gathered, combined, sorted, and sold to industrial mills, and the wool pool managers distribute the funds… But imagine if it was all processed by small scale mills—think how many people we could employ, the quality of hand made wool products, and the beneficial environmental impacts. I started off my adventure by looking through my fiber to check for moths as I always do. Passed the test 😂 so into a hot wash of 125+ F water and Unicorn Power Scour with lavender essential oil. After three washes in my salad spinner, I dried it on my solar (diffused) drying rack for 18 hours. I combed it on my wool combs and the rest of the Vegetable Material (VM) fell out easily (wear an apron!) combing was a little difficult because the fibres meshed together really well with their kinky crimp. I had actually been working on several combing and dizing projects, so my hand STILL HURTS… dizing was also hard to get started (I pulled the wool through a hole in a seashell to pre-draft, prep the fibre so it will be easier and neater to spin) but once I hit my sweet spot, the fiber came off beautifully into a lovely combed top. I spun most of the combed top into a beautiful, lofty skein probably a DK weight yarn. After it was finished, I dyed the yarn and remaining fibre in Cushings Perfection Acid Dye and washed it clean, leaving it to air dry after a spin in the salad spinner. With the remaining fibre, I carded some rolags and spun it up on my new-to-me 1800’s Great Wheel spinning wheel. The Suffolk wool was very well-suited to the great wheel due to its short staple length and general poofyness. (That is a technical term—okay fine, loft). I was very happy with each of the steps of this process and am very glad I was able to do this experiment and share my experiences with you! Hope you enjoyed the wool of the week Suffolk edition 💙💙💙 Where I’ve been Hi! If you don’t already know me, I’m August Lee—a fiber artist, gardener, homemaker, nature lover, and Kentuckian. Born in Georgia, I moved home in 2006 to Louisville, where my dad’s family settled in the US after coming over from Germany way back when. Farming with a capital “F” is not in my near-blood necessarily, but EVERYBODY in my close family gardens, every spring, every summer, dropping off zucchini and tomatoes and beans to each other, sharing the bounty with friends and neighbors, it was and is a part of our culture. When I was little, my mom read my sister and me the Little House on the Prairie books, and that world, that life grabbed at my heart. I stood in my garden and climbed up the tree and played in the creek and was a wild child. I had no idea what was coming with the rise of the smart phones and personal computers, now to Apple Watches and Google Glass. Laura Ingalls never had an iPhone… But one of my grandmothers was raised on a farm, and at the end of her life, was remarried to a farmer in rural Georgia growing her top favorite foods, blueberries and figs. Bobbie was my favorite grandparent, and I was inspired by her passions—hummingbirds, daylilies, and her sweet, wild barn cats. I read a book, Home Economics, by Wendell Berry, and it was a wake-up call for me. “You can find purpose and meaning” I heard the country calling—now I wanted to be an all-American kid (can ya hear Arlo Guthrie?) i wanted to go out into the fields and become a part of the landscape, timelessly embedded in the moving ecology of the farm, and just BE there. Not only did I feel like it was a respectable thing to be doing—it makes sense and people can usually understand it—but it also felt like a life way that would allow me opportunities to do most of the things I really care about. Farming careers are very diverse and run the gamut, there’s not just one type of farmer, and each farmer isn’t probably even a single type of farmer. I knew I wanted to work with the earth and live off of the land in some way, but I wasn’t sure where I fit in until I discovered wool and fiber farming. At Appalachian State Univ, I studied sustainable development from sustainable agriculture to being a good neighbor, and then transferred over to the Wendell Berry Farming Program of Sterling College (VT) when I won a full tuition scholarship to finish my degree in sustainable agriculture and draft animal power systems— “a degree in homecoming”. I moved home to KY and drove two counties away to school in Port Royal, Henry County, for classes. It was a small program of driven people who were hungry for learning and skill building. Very soon into the program we were taking trips to farms all over the state, learning the whole-farm realities of the 24hour a day job that is farming. How to live the actual life through a lifetime. I found my niche in the world of wool through spinning, the act of making yarn from plant or animal fibers. (This was, yes, my pandemic craft.) This expanded and then blossomed quickly into other culturally related heritage crafts (sewing, quilting, basketry) and direct farming skills (rabbit care, sheep shearing, washing raw wool) as well as building basic business skills as I did some of my first farmers markets and art shows. I joined several guilds during the comeback from the pandemic including the Louisville Nimble Thinmbles quilt guild, the Friendship spinners Kentucky fiber guild, a local knitting circle. It really has changed my life being able to learn from and with other people in real life and see what their techniques are and learn what their passions are and to hear their stories. Where am I today? What are the practices I incorporate into my routine? What are my current values? As I write, it is 2023. I graduated college two years ago, and have been working on my small business, the Emerald Garden Girl, off and on as I explore business plans for my future, and explore how I can use my current small business as a stepping stone to all of these landmarks I dream of accomplishing in my future. My active mission includes providing free online fiber arts education, but I also offer by-appointment in-person classes, and sell a variety of fiber homestead products. I live in a neighborhood in Louisville, which doesn’t allow chickens and you have to cut your grass and such. I attempt to cook most of our food at home, and unprocessed. However, some weeks “most” is a lot less than other weeks. It’s a constant battle but we keep at it! I try to buy (again) most of our groceries as whole food ingredients (so, I would instead of buying crackers, buy ingredients to make crackers, or instead of buying salsa, buy ingredients to make my own.) I try to buy as much as I can at farmers markets when the pocketbook allows (and sometimes you SAVE money at the farmers market!) I have started playing with switching to Dr Bronners laundry and Dr Bronners hand and dish soap. I wash my body with Bronners, shave with Bronners, and rinse in diluted Apple cider vinegar. I use rose witch hazel as deodorant. I use calendula balm as ointment. I use homemade tallow lip balm (and I rendered the local tallow). And skin-safe, diluted essential oils as scent. I keep clothes buying and purchases in general to a minimum, refuse additional plastic packaging, come equipped with reusable totes, recycle (and try to recycle within the household). Where I envision and am working towards going with my homesteading career I dream of having a family and living off of the farmstead with a market garden and various animals which will nourish us, supplement our income, and serve as bartering and gifts. I believe food is most nutritious when we not only fertilize the plants with nutrients as they grow or provide a complete diet to your livestock, but also when we invest our time, care, and love into these beings. I want to know my meat, when it lived, was loved and felt that love, and knew its importance and goodness, and knew my thanks each day, and first received what I give back to it and enjoyed the benefits of my care. I want to be a good caretaker. I want my meat to have lived happily and healthily, and to be treated with dignity. And even though I don’t have meat animals I raise now, I want to meditate upon this and meet the challenge of actually doing the thing, for what it is, and embrace the struggle and the suck when it does happen so that I can overcome it as I learn. I am learning to take grace when and where I can, to walk into this world gently. If something like butchering is too much, can I just do one part of it? What parts don’t bother me and why do the parts that bother me actually affect me.

I hope to have my own fiber animals (various sheep, alpacas, and angora rabbits) when I am located at land that has suitable infrastructure to care for these critters. I want to use their fiber along with a small-scale, in-home wool mill to process my wool and then hand spin it into yarn to be dyed and sold. I will also use this mill to process other local wool from local producers for those producers to use. I want to build up my fiber arts education on my social media platforms and this website, but also as in-person classes with both modern and historical spinning techniques and tools. I want to grow my skill base so I can provide well-rounded educational offerings in the fiber arts including quilting, sewing, knitting, crochet, weaving, spinning, dyeing, fiber prep, sheep shearing, sheep raising, fiber gardens, dye gardens, basketry, willow creek bed remediation, etc. And boy, wouldn’t it be cool to grow this hub of education into a rural arts and culture center with other historical and modern folk arts. On a diversified, small scale, draft-powered farmstead. One step at a time. 🥰 |

Quilt Update!

IronweedDisco Chicken of Love

sTate fair ready!seed starting 2019ky state fair quiltWHOTH Embroideryseashell casTleswhoth blanketedible goodnessAuthorA sustainability major at U of L, beginning farmer, crafter, and writer. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed